Different ways to capture a choir… including a stereo miking trick everyone should know

By Justin Peacock

“I love to hear a choir. I love the humanity to see the faces of real people devoting themselves to a piece of music. I like the teamwork. It makes me feel optimistic about the human race when I see them cooperating like that.“—Paul McCartney

Few other musical instruments are more organic than the original: the human voice. A choir, the sum of many voices, has to be one of the most familiar and recognized ensembles in music. Perhaps you first think of classical music with choral groups, but gospel, pop, rock and beyond can all incorporate a large group of singers, adding incredible energy to a track. Here are some techniques to get your started on your first choir session.

Let’s get practical…

Before 50 people show up at your studio waiting to start recording, there are some practical issues to take into consideration.

First, can you jam this many people comfortably into your space? Will they be packed like sardines? Can your air conditioning keep this many warm bodies from overheating?

Do the singers need music stands or do they hold their music? Are they practiced at turning pages quietly? Do they need risers or stools to provide vertical separation? If you’re overdubbing the choir to preexisting tracks, do you have enough headphones and amplification to drive that many head sets?

The arrangement

An important aspect of the sound you get revolves around the arrangement of the singers in the room. In traditional classical music, the sopranos, altos, tenors and basses (SATB) will often be in separate sections, spread out left to right.

Depending on the direction of the conductor, it’s typical that the sections will be mixed together in various ways to create a blend. Checking in with the conductor can give you a heads up on what to expect.

Keep your distance

Once the choir is in place, it’s time to get your microphones into position. The name of the game here is equidistance.

Rather than as a group of individuals, it’s best to think of a choir as one entity. Like with a piano, many individuals make up the whole, and we don’t record a piano with one mic on every string! Instead we use a simple array, like a stereo pair, to capture the whole.

With this in mind, it’s important to keep each vocalist roughly equidistant from the microphones. This will typically yield a semicircle, as it’s geometrically the best way to achieve a balanced arrangement.

Balance the bodies

Once you have your choir set up, your next task is to balance them. A good choir can balance themselves in a truly amazing way, making short work of your recording. But it’s often the case that an individual singer or a section of singers is either too loud or too soft. In such a case you can remedy the balance problem by simply telling (nicely, of course) the offending section or individual.

If that doesn’t work, or if there is an unbalanced number of singers in a particular section (ie: 2 altos called in sick and the sopranos are way too loud) then simply move the bodies around. In our example problem, try having the altos take a step forward and the sopranos a step or two back. Some of these minor adjustments can greatly improve things.

One choir, not one voice

Rehearsing the choir is probably not your job, but making them sound good on tape is. Consequently, it’s important to ensure that your microphone array is not reinforcing a particular singer over the sound of the ensemble.

The mark of a good choral group lies in their ability to blend perfectly, so that no one individual can be picked out from the group. If one microphone is too close to an individual, for example, you can ruin this crucial balance.

Two to start

Any of the stereo microphone techniques can be successfully applied with a choir. Here are some thoughts and considerations to get you going.

- XY stereo, using two coincident (one capsule above the other) directional mics angled at 90 degrees, works well for overdubbed choir parts—a choir track recorded over a rock band, for example.

- ORTF stereo uses two directional mics pointed away from each other in a wide “V” shape. Though you can vary the angles and spacing to suit your purposes, the starting place for this technique has the capsules spaced 17 cm (approximately the distance between your ears), angled apart 110 degrees. This creates a wider image than XY stereo, and is therefore more pleasing with unaccompanied choir.

- Spaced Omni stereo employs 2 omnidirectional microphones spaced apart significantly further than the other techniques. For larger groups like choirs, I usually start around 3 feet, and work the mics a bit closer. I love this technique, and you will too!

- M/S (Mid/Side) stereo is underused and not always understood. M-S stereo is fantastic in that you can adjust the width of the stereo image, allowing either wide stereo or a focused center. If you’ve never used M/S before, here’s a quick tutorial:

Mid/Side for beginners

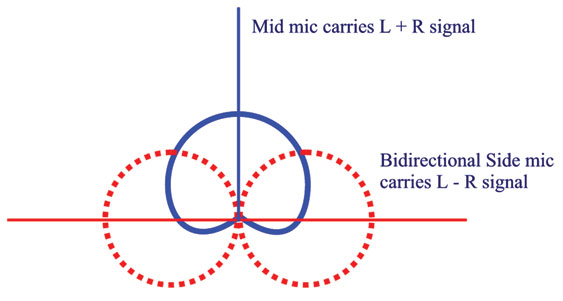

Mid/Side (M/S) stereo is a unique approach to stereo miking, and is a lot of fun if you’ve never tried it. To get started you’ll need 2 microphones, one directional (cardioid is a good place to start) and one bi-directional (figure-8).

Set up the mics so that the cardioid mic (the Mid) is pointed straight ahead. Right above the Mid, setup the bi-directional (Side) microphone turned 90 degrees sideways. Make sure the front of the Side microphone is aimed at the left of your soundstage. The front of the Figure-8 mic will generate the left channel, and the rear will generate the right. (See the figure at left.)

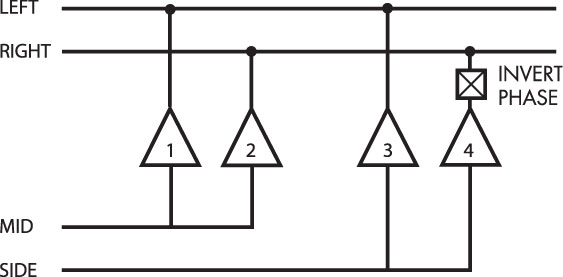

Using a “Y” cable or by duplicating the side track’s output in your DAW, split the Side channel so that you have two copies.

Using a plug-in, a console’s invert switch, or an analog cable with pin 3 wired hot, flip the polarity of the secon d duplicate channel. (See the figure at right.)

d duplicate channel. (See the figure at right.)

Pan the two Side tracks hard left and hard right. (If they are both panned in the center, you should hear full phase cancellation and therefore no audio from them.)

Bring up the Mid mic to complete your stereo!

The relative level of the Side channels to the Mid mic will change the width of your stereo image. Turn them up and down until you find a blend that’s suitable. You’ll notice that bringing the Side channels down completely leaves you with a mono Mid signal; this makes mono compatibility in M/S the best of all possible stereo mic setups, because summing your stereo mix to mono will cause the two Side signals to cancel each other out, leaving the Mid.

Three’s company

Here’s a case where three is not a crowd. Probably my favorite array for choral groups, three mics spaced across the front, yields excellent results while allowing several distinct advantages. Primarily, setting the choir up in a semicircle is not necessary. In a church, for example, there is often not enough room for the group to arc around, as the front pews are in the way. The singers end up in more of a block, perhaps 4 or 5 rows deep.

Additionally, the spaced microphones, accordingly panned hard-left, center and hard-right, provide a wide stereo image with a good center foundation. You can use three omnis, 3 wide cardioids or even 3 cardioids for pinpoint imaging. For particularly large groups this technique can be expanded to 4 microphones.

Best of both worlds

Now that we’ve discussed both stereo and three-mic arrays, we can explore a great way of combining methods for a best-of-both-worlds approach: M/S with flanks.

In this setup we use an M/S stereo pair in the center as our foundation, and flank it with 2 mics on the sides. Starting with essentially the same mics as the three-across-the-front method, we’re simply adding a figure-of-eight mic at the center position to create M-S.

On a recent project I used this type of 4-mic stereo array, giving myself excellent flexibility. Primarily the director was concerned with reinforcing the stronger singers who stood at the center of the group. With the M/S pair I was able to achieve a narrow stereo image focused on the stronger singers in the center, widening the mix with the flank microphones. Additionally, the choir was divided by sections, the flank microphones giving me control over the relative balance of the alto and soprano parts.

Highlights and so-lows

With careful balancing and placement of mics you should be able to achieve a full and good-sounding choir recording. However, there are times when certain sections need to be slightly reinforced, or solos to be brought out in front.

For soloists, simply stepping out in front of the choir can often “turn them up” enough, preventing the need for a solo spot mic. If it’s not enough, however, then a spot mic can be applied.

If this mic (or any highlight) is placed in a section, you have severe potential for phase cancellation due to the fact that the soloist’s voice will first arrive at the spot microphone, then at the main microphones. To prevent bad sound, simply apply a time adjustment delay to the solo track. If you measure the distance from the solo mic to the nearest main microphone, you can calculate the approximate delay time. Simply divide this measurement by the speed of sound to get the delay amount.

How fast does sound travel? Well, it depends on the air temperature and the relative humidity, but 1100 feet per second is a good place to start. This increases as temperature and humidity increase. Once you have your delay amount dialed in, use your ears to determine the best sound, nudging back and forth ever so slightly.

Sometimes the other “so-low” needs some reinforcement. The bass section, depending on its size and strength, is often weak, only because many choirs have difficulty finding enough men with exceptionally low range. To help them out, try a mic placed among the basses. Use a low-pass filter to remove the high frequency, leaving you with a nice bass fundamental. Just a bit of this can help the bottom extension of your recording and improve the warmth and fullness of the choir.

Experimenting with these techniques should give you a good start on choral recording, as well as other large-ensemble methods. You can use these ideas with orchestras, chamber groups and duets, as well as individual instruments. Happy recording, and Hallelujah!