Engineer and educator George Petersen tracks a piece of recording history from a garage sale back through time

A $20 find at a local flea market yielded an unexpected score: a vintage mastering equalizer built by Motown Studios.

By George Petersen

I’m one of those people who’s hooked on history. As a lifelong audio rat, I’ve developed a keen interest in our audio heritage, which I’ve expanded into an ongoing 900-page book project on the roots of audio technology. I also serve as the director of the TECnology Hall of Fame, which I founded 10 years ago as the historic off-shoot of the TEC Awards.

I’m also a flea market junkie. You never know what you might find in such places, but a year ago, I stumbled across an item that intrigued me and set me on a path of audio discovery. Piled in the corner of a stall at a flea market in Oakland, CA, was a large, odd-looking rackmount chassis. On closer examination, it was a single-channel 7-band passive equalizer. It had no manufacturer marks, although the engraved front-panel markings on the aluminum front panel were obviously professionally done. The seller didn’t offer any help, but informed me (in Spanish) that it came out of a storage auction sale and he wanted $30 for it. I offered $20, which he accepted. See Picture 1 for my find.

At first I wondered whether this was a prototype from Pultec, Langevin or possibly Universal Audio. Figuring out exactly what it was proved to be somewhat of a mystery—or, as Sherlock Holmes would say, “the game’s afoot.”

Inside top view of the Motown Mastering EQ shows a clean, handwired design, with Electrocube capacitors and carbon composition resistors. A second (similar-looking) circuit board is viewable only by removing the lower cover. Not visible are the inductors, which are mounted under the circuit boards.

Unlocking the mystery

Getting it home, I took a few notes and popped the covers for an inside look, as shown in Picture 2. It’s an LC equalizer design—meaning its frequency response changes are made via routing the signal through a network of capacitors and inductors (the latter are sometimes also referred to as chokes or coils). LC circuits are found in all kinds of audio devices, from speaker crossovers to vintage studio tools, such as the Pultec EQP-1 equalizer. This mystery EQ is also a fully passive design with no active gain makeup stages; such devices typically demonstrate insertion losses that can range from about –2 dB to –16 dB. Therefore, most outboard passive filter designs include some kind of amplification circuit to compensate for any signal attenuation.

The frequency centers of this particular equalizer are identical to the famed Motown Studio EQ (50/130/320/800/2k/5k/12.5k Hz), with ± 8 dB boost/cut in 1 dB steps, in/out hardwire bypass switch and channel I/O on a barrier strip. The Motown Studio EQs are 2-rack-space boxes with an onboard gain makeup stage, and some 40 of these were fabricated to Motown specs for the label’s studios in 1968 by Protofab of nearby Troy, MI. However, the EQ I had seemed different than those—it was a 4-rackspace unit with a global switch that drops the center points of all the frequency bands by 50%.

Inside was a lot of intricate and beautifully done point-to-point hand wiring, from the mil-spec stepped switches and resistor ladders to two custom Fiberglas circuit boards with toroidal inductors mounted on the underside, along with Electrocube capacitors and carbon composition resistors. It clearly wasn’t homemade, although it could have been a custom one-off built for a studio or mastering facility.

Still intrigued, I posted images of the unit on Facebook and thanks to some help from producer Ron Saint Germain and studio guru/former Motown engineer Tony Bongiovi, my unit was confirmed to be a mastering equalizer custom-made by the in-house technical engineering shop at Motown Studios. Moreover, they offered to put me in touch with Motown engineer/chief tech Mike McLean, who built much of the gear at Hitsville USA.

McLean began working at Motown at age 20 in January of 1961—just six months after the company formed—and remained on staff until 1972. (See Picture 3.) He’s a friendly guy and was glad to share a few memories and insights into the technology and process that drove Motown in the early days, as well as help solve some mysteries about my equalizer.

Mike McLean with the Motown custom 8-track recorder.

Disk cutting: a secret revealed

Back to the mystery equalizer that got me started on this quest for early Motown history, McLean verified the EQ I bought was indeed from Motown’s disk cutting room. But the real surprise came from his explanation about the “half/normal” frequency switch in the lower right corner of the front panel. I had originally thought that this was merely a way of offering additional frequency options beyond its seven bands. But in a quest for increased fidelity and “hotter” releases, Motown was doing half-speed mastering in its early days—a process that I was not even aware of until it began to rise in commercial popularity in the late 1970s.

“We got into disk cutting fairly early on,” McLean explains. “We’d cut test reference acetates, so they could compare that to other records to make up their mind if the mix was right; and we would cut lacquers, which were used for disk pressing. The first of our tape-to-disk transfer rooms was intended to meet Motown’s needs at the time, which were: low cost, mono-only and the best quality possible. However, there was no preview-controlled variable pitch and depth (this arrived at Motown later), as pop records had only one level, which was loud!”

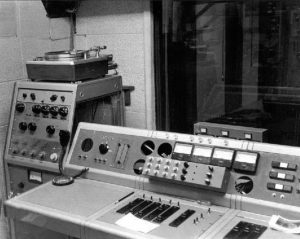

Motown’s console in 1964 consisted of a modified 1939 Western Electric mixer, supplemented by two rackmount submixers: a 4-input Ampex MX-10 (seen in bottom of slanted rack on the left of the photo) and a 5-input Altec 1567A mixer (not visible here), which was located in a rack behind the mix position.

Shown in Picture 5 (below) is Motown’s mono disk room. It had a Neumann AM131 lathe with a Neumann/Teldec type ES-59 cutter head and a Studer C37 tape machine. “In the upper right side of the picture you can see the Type One—the kind that you purchased at the flea market. It provided everything we needed—it was a single channel mono unit, with selectable frequencies for half- or normal-speed cutting. The two Type One units provided for cutting mono album masters. The upper unit seen here was used for setup 1, 3, 5, 7, etc. (the odd-numbered selections on the LP disc), and the lower EQ unit was used for setup 2, 4, 6, 8, etc. (the even-numbered selections).”

The process was complex and required some quick timing. “There was also a lot of paperwork to keep track of the various versions and changes,” McLean adds. “You went to cut the LP with six or seven cuts on each side, each with different equalization settings. Then you’d have to preset the second set of equalization for the next song and switch back and forth. It could be a nightmare.”

“The Westrex cutter that everybody else was using had a resonance at the high-end that was bad for naturalness of sound but very good because it took the heat off the drive coil. You could push those about as loud as you wanted, because in that sense, that resonance was working for you,” McLean explains. “The Teldec cutter was pure, sweet and resonance-free right out to 20 kHz, but had nothing to give you help on that power requirement. The solution was a converter for the Neumann lathe that made it run at half speed, so all you had to do was run your master tape at half speed and fix the equalization.”

Motown’s first record cutting room had a Neumann AM131 lathe and a Studer C37 tape playback machine. In the rack at the top right of photo are two of the 7-band Type One mastering equalizers built by Mike McLean.

The latter step required taking all the EQ settings from the mastering notes and cutting the values of all the center frequencies in half, so for example, a –3 dB cut at 320 Hz would become a –3 dB cut at 160 Hz; +4 at 5 kHz would become +4 dB at 2.5 kHz, etc. Of course, later, on full-speed playback, all the frequencies are doubled, the program plays back at the correct speed, and your mastering EQ changes occur at the right frequencies. The net effect of the half-speed mastering process yields more recording level without overheating the cutter head and/or clipping the recording amplifier. “We tried it out and indeed did find out that it let us increase the maximum level by 8 dB, compared to what it was,” McLean notes.

A solution for this would be an equalizer with a single switch that globally reduced all its center frequencies by 50 percent, which required a custom unit. “I began with the Langevin EQ 252a graphic equalizer design by Arthur C. Davis. We then built something based on the same schematic—but different packaging, better switches and all that, because we wanted half-speed frequencies as well as the full-speed.”

The stereo mastering setup at Motown, with two banks of 7-band EQs used for stereo L/R and a single mono equalizer. The large knob on the right (beneath the four VU meters) was the transfer control used to switch between the two banks of EQs during a mastering session.

Several versions of the mastering equalizer were made. “The two mono units could be switched from full-speed to half-speed; 2-channel equalizers were later made for the stereo disk cutting room. The changeover switch itself was a hell of a component with about eight decks on it to switch all those LC resonant circuits on those resonant circuits. On full-speed, it would route through one set of capacitors and chokes—which provided the correct frequencies—and for half-speed, it would toggle to another complete set of elements to provide the right frequencies for half-speed.”

Eventually, Motown added a room with stereo disk cutting capability, and the process of half-speed mastering to cut stereo releases became far more complex. The new disc cutting room featured a Neumann type SX68 cutter head and Neumann AM 32B lathe, which was equipped with preview-controlled variable pitch and depth of cut.

“The stereo room had its own set of problems, because it not only had to switch for left and right channels of the program but also the preview feeds for the new variable-pitch and depth Neumann lathe. The preview feeds had to be equalized, along with the program material. So for stereo, you’d need two EQ channels (left and right) for the program, two more equalizers (L/R) for the preview and then four more equalizer channels for the next band on the record. Constantly resetting each set of four EQs for the next cut, over and over on an album [while the disk was cutting] was a hell of a mess.” Pictures 6 and 7 show the EQ racks and the console.

Close up of the stereo mastering console at Motown, which—with its Dymo Labelmaker markings—was built for performance, not looks. It allowed switching between mono and stereo modes, as well as monitoring different sources and tweaking the cutter head’s preview and program feeds.

A mess? Perhaps. Complicated? Certainly. But the right combination of a dedicated crew, talented producers and engineers, great artists, memorable songs and the leadership of Berry Gordy all made an indelible stamp on the world. And the rest—as they say—is history.

History revealed

If gear could talk, what tales they’d tell. And here was a processor that handled hundreds of mastering sessions on classic Motown releases. Of course, you never know what treasures lie at the next garage sale, swap meet or flea market, but the process is kind of like fishing. Even if you don’t snag anything, it’s still fun to go out and drop your hook in the water… because you never know what you might reel in. Give it a try!

George Petersen ([email protected]) is the former editor of Mix Magazine and currently runs FRONT of HOUSE, a publication for the live sound and touring industry.